How Isaac del Toro and UAE Team Emirates Lost the Giro d'Italia

In which my old game theory textbook does more work than three domestiques

I’m back from the woods, and as I suspected, there have been Events.

I’m going to go ahead and assume that if you care enough about cycling to read this newsletter, you already know what happened in the last competitive stage of the Giro d’Italia. And if you didn’t know before this email showed up in your mailbox, the header photo of Simon Yates in a pink jersey spraying sparkling beverage at the Giro d’Italia trophy is probably a good clue.

Isaac del Toro hit the Colle delle Finestre—the biggest, meanest, most gravelly mountain in this race, the one we all expected to be decisive—with about a 40-second lead over second-place Richard Carapaz, who himself had about a 40-second lead on Yates.

How, then, did Yates come to the end of the stage—and, 24 hours later, the Giro—with a lead of three minutes and 56 seconds on del Toro? Like, we know how it happened, but how does it make sense?

Every road cycling race is determined by a combination of two factors: The individual rider’s strength and fitness on one hand, and tactics—both the rider’s decision and the team’s orders—on the other.

Over the past few years, many—I’d even say most—of the big races have been decided by the former consideration. Tadej Pogačar or Mathieu van der Poel1 eyes up a hill he likes, puts in his earbuds, queues up “Ebolarama” and off he goes. This Giro was the opposite.

I’m not going to act like Yates didn’t have great legs over these three weeks. He was right there at the sharp end as, one after another, guys who are used to finishing in the top 10 of grand tours2 crashed or cracked. This was about as strong a GC startlist as there’s going to be without Pogačar, Jonas Vingegaard and Remco Evenepoel, and Yates stood alone.

But he didn’t win because he was the strongest. He won because he, and his team, avoided making a fatal tactical mistake.

Heading into the Finestre, Carapaz needed to get 40 seconds on del Toro, who not only had the lead in the race but by far the strongest array of domestiques to help him. But the Finestre is so tough, that’s doable. Easily. In a straight fight, up the toughest mountain in the race, on the last Saturday of the race, Carapaz can take 40 seconds out of almost anyone.

So EF threw all of its team power into isolating del Toro. They rode four or five at the front, led by Kasper Asgreen and his gigantic, good-enough-to-wear-out-van der Poel engine. They were going so fast at one point they overcooked a corner and almost went either into a set of trash bins or over a cliff in a five-man Flying V formation.

They got to the foot of the Finestre, call it 50 kilometers from home, and ran a sprint leadout train to get Carapaz going uphill as fast as possible. They shed the bulk of the peloton. Then the back half of the GC top 10, along with the key UAE climbers: Adam Yates, Brandon McNulty and Rafał Majka. Then they dropped Simon Yates, and finally del Toro.

The young Mexican got back on Carapaz’s wheel fairly quickly, but Carapaz then had about 16 kilometers, at this point, to make the move stick. And he’d already dropped him once.

This was the ballgame for EF. The boys in pink had spent all their domestiques early so they could get their leader one-on-one with del Toro, with enough real estate between them and the top of the Finestre to gap him.

If it were a time trial up the mountain, or a heads-up match race, I bet Carapaz wins. When his attacks didn’t stick, he stopped riding tempo and slowed down, which is what you’re supposed to do; why ride tempo and let del Toro get a free ride?

Only by this point, Simon Yates—who fell 20-odd seconds behind in the first pitches of the hill—was able to catch up.

Yates needed something weird to happen in order to not only distance Carapaz but del Toro as well, and this is where he got it. While Carapaz and del Toro did game theory at each other, Yates drifted back with the guys who were fighting it out for the lesser GC placings, a group that included the three aforementioned UAE domestiques.

But when Yates set out after the two leaders, none of the UAE riders followed him. Majka, McNulty, Adam Yates—they all were either uninterested in marking Simon Yates, or unable to follow what looked to me like a pretty mild acceleration.

If one of those guys holds Yates’ wheel, suddenly del Toro has an ally on the hardest climb of the day. Someone to help wear out Yates and Carapaz, or to bridge the gap if one of the two escapes. Not getting a domestique on Yates’ wheel was tactical failure no. 1 for UAE.

Tactical failure no. 2: The two-man game of chicken became a three-man game of chicken. And when Yates finally punched out a few bike lengths’ lead, then stretched it to a multi-second advantage that started to grow, Carapaz and del Toro looked at each other. Neither one wanted to do all the work to bring back Yates, then get left for dead and lose the Giro.

Yates stretched his lead out to 40 seconds, and for a while Carapaz rode tempo with del Toro behind, but del Toro put in almost no effort of his own. Which was not only a fatal mistake in retrospect, it was a naive decision at the time.

3With Yates up the road, del Toro and Carapaz were in a situation best expressed as a strategic-form game. I’ll quote from my textbook:

A strategic game (with ordinal preferences) consists of:

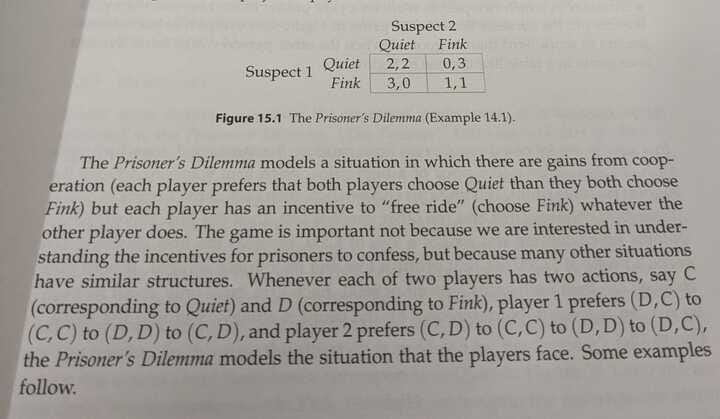

There are a few basic examples of strategic-form games that every student gets taught, depending on the incentives to cooperate and the disincentives of defecting. But the very first one in my textbook is not only the one you’ve all heard about, it’s the one that describes Carapaz and del Toro’s situation best:

In the textbook example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the outcomes are symmetrical for each player. I’d argue this is not the case for del Toro and Carapaz.

If they’d worked together, they probably would’ve caught Yates and fought out the Giro between themselves, with the rider who did the least work at an advantage. If Carapaz does the work and loses out to del Toro in the end—or even fails to beat him to the line by 40 or more seconds—he’s done nothing to advance his cause. Conversely, if Carapaz defects and they both founder, which is what happened, he drops from second to third on GC.

I don’t know if this is how Carapaz approached the issue, but if I were him, I would not have given one single shit about finishing second or third. This is a guy who’s already won a Giro. He’s also already lost the Giro by 78 seconds once, and lost the Vuelta by 24 seconds. EF is not a team with regular grand tour GC ambitions. Carapaz’s third place at the Giro was EF’s best grand tour GC finish since 2020. This team’s been around since 2008, and they’ve only podiumed a grand tour five times. And that’s if you count Bradley Wiggins getting bumped up to third place in the 2009 Tour de France after Lance Armstrong got DQ’d. I don’t think the sponsors care much either, if Carapaz finishes second or third and there’s a win on the table. And unless Derek Gee took enough EPO the night before to turn his blood into clay, Carapaz was staying on the podium.

Del Toro, by contrast, had everything to lose. Or at least: the maglia rosa, which would for sure 100 percent be going on a one-way trip to Visma-Lease a Bike’s team bus if neither he nor Carapaz worked. You don’t want to be the sucker, do all the work, and get nut shotted on the way to the finish in Sestriere. I get it.

But once Carapaz defects, del Toro has to, has to, has to get on the horse and chase Yates down.

Of course, the Finestre was not the last climb of the day. After descending the big gravelly mountain, the riders had a gentle uphill climb to Sestriere. Probably not challenging enough to be decisive if all three favorites came to the foot together and in good condition, but in a Giro that looked like it was going to come down to a handful of seconds, said handful could be found here.

If Carapaz, Yates, and del Toro had been the only three riders left on the road, the two chasers would’ve had a major advantage with that much open, relatively flat road ahead.

But they weren’t.

Stage 20 started with a breakaway of about 30 riders, from which came the stage winner, Chris Harper of Jayco-Alula. Ultimately two breakaway riders finished ahead of Yates, and six finished ahead of the del Toro-Carapaz group.

It was abundantly clear to me, even before the summit of the Finestre, that del Toro and Carapaz weren’t going to work together, and that their collective intransigence would hand the race to Yates. But it helped that Yates was the only one of the three whose team put a teammate in the break, and that said teammate was Wout van Aert.

Certainly that’s why the winning margin ended up being around four minutes.

I want to underscore how hard it is to do what van Aert did on Saturday. To spend all day in the break, to get over the Finestre ahead of the GC group, with enough left in the tank to pull on the gentle uphill between the two last climbs, and then have enough left in the tank to drill the tempo on the final climb, and have enough power to make a dent in the two guys who had been dictating the race for the past week. On a mountain. After three weeks of racing.

That’s not a typical climbing domestique’s job. Majka can’t do that. Sepp Kuss can’t do that. Asgreen, for all his power on the flat, would’ve had trouble on the uphill sections. If EF has a rider with that toolkit on their entire roster,7 they didn’t bring him. Certainly nobody comparable to van Aert.

Because the list of riders who could do what van Aert did, as powerfully as he did it, and have the mindset to work for a teammate like that…it’s a very, very short list. I’d have trouble naming five guys like that in the entire world.

But I can name one: Brandon McNulty.

Who was in this race, working for del Toro, one group back on the mountain. And while van Aert put the race on ice for Yates, McNulty was in a position where he was of zero, absolutely zero use to del Toro.

Why couldn’t UAE have put McNulty in the break, as Visma-Lease a Bike did with van Aert? Because he was the only UAE rider, apart from del Toro, who hadn’t blown up and slid out of the GC picture before Stage 20.

Saturday morning, McNulty woke up in 10th place overall, nine minutes and 33 seconds behind del Toro. Even in one of these big, no-loads-refused Week 3 breaks, there is an art to choosing which riders are allowed to get away. McNulty, almost 10 minutes back on GC and two and a half minutes behind eighth-place Einer Rubio of Movistar, was never going to climb the standings on his own.

But that big-ass breakaway spent most of the afternoon eight or nine minutes ahead of the pink jersey group on the road, and hit the Finestre 10 minutes before the EF convoy. A gap that big would’ve put McNulty in the virtual GC lead. Even going five minutes ahead would’ve lifted McNulty from 10th to sixth, much to the chagrin of the four teams’ lead riders he would’ve passed on the road. Those other teams would’ve ridden themselves inside-out to stop that from happening.

So for McNulty to be viable as a satellite rider, he would’ve had to lose major time earlier in the week—a sacrifice that might’ve helped del Toro, but giving up a top-10 grand tour GC spot is a big price to pay for the opportunity to maybe play a different tactical card that you’re probably not going to need anyway.

Could UAE have used McNulty to mark van Aert, in an attempt to keep him out of the break? Maybe, but that would’ve sapped energy from a key mountain domestique early in the stage. The same if UAE had used Adam Yates or Majka for the same purpose. And with Juan Ayuso and Jay Vine having abandoned earlier in the week, UAE was down to six riders, including a leader and an inviolable three-man mountain train.

I understand why they couldn’t do it, but not having a way to neutralize van Aert was the final tactical mistake that did del Toro in.

Not that I think it would’ve mattered. By the time Yates hooked up with van Aert on the descent of the Finestre, the game theory boys had fucked around so much their deficit was at 1 minute, 45 seconds.

With no van Aert out front, and McNulty towing del Toro, maybe UAE could have pulled that gap back. Carapaz, having used up all his domestiques 20 kilometers back, was done for by this point.

As it was, van Aert put another two minutes into the leaders before he gassed, and del Toro, well, he gave up. It was over. He’d lost the Giro, and whether he lost by 10 seconds or 10 minutes mattered little.

Simon Yates winning the Giro is not just one fascinating story, it’s several. He’s Visma-Lease a Bike’s fourth different grand tour winner in the past seven grand tours. He won this race on the very mountain where, seven years ago, he blew up and lost it in one of the most famous one-day reversals in cycling history. And with six and a half years since his win at the 2018 Vuelta, Yates has the longest gap between grand tour GC wins that I could find, not counting riders who had their careers interrupted by a world war.

I probably would’ve preferred to see Carapaz, my favorite GC rider, take a second Giro. Or to get to say “I told you so” about del Toro, whom I’d been hyping up since his World Tour debut last January. But getting a historic win, thanks to one of the wildest hours of stage racing I’ve ever seen, is a great consolation prize.

Because this is why I love cycling so much as a spectator sport. It’s the ultimate test of fitness and nerve. You wait for weeks for something to go wrong, and then when it does go wrong it happens in an instant, and also in slow motion. It’s an intellectual challenge: constant mental algebra to figure out who’s at an advantage, while balancing the tremendous emotional weight of empathizing with these emaciated weirdos as they suffer crushing mortification, in the colloquial and the Catholic sense, both at the same time.

Or sometimes Filippo Ganna or Jonas Vingegaard or Remco Evenepoel, but usually Pogačar or van der Poel

Yates beat five former Giro GC winners: Carapaz, Primož Roglič, Jai Hindley, Nairo Quintana and Egan Bernal.

Going to grad school was a mistake, sure, but not getting rid of all my textbooks from grad school, lugging them through five cross-country moves in eight years? Best decision I ever made.

del Toro and Carapaz

Ride or coast

Most preferred: Win the Giro. Second-most preferred: Finish second. Least preferred: Finish third.

Maybe Neilson Powless?

It's been my first non-TdF race of meaningfully following, and I think I'm hooked. Loving your posts and especially this one!

What type grad school topic was it? Any other text book recommendations? Wish I kept mine!!