In contrast to Tuesday’s post, which broke down the slightly harder-to-follow points classification race, the general classification at the Tour de France is simple enough to figure out.

Over 23 days, 176 riders will follow a course of 21 stages, totaling 3,498 kilometers across four countries, with 52,230 meters of climbing. That’s the equivalent of New York to Phoenix horizontally, and nearly six trips up Mt. Everest vertically. Whoever does all that in the shortest cumulative time1 gets the yellow jersey: the most prestigious prize in cycling and the most recognizable bit of sportswear anywhere.

Simple enough.

But these guys don’t just race flat-out every moment for three straight weeks. Cycling is an individual sport that’s most efficiently contested in groups. (Again, for newcomers to the sport, see my Crash Course in Cycling post on why that’s so.)

That means the handful of riders who care about their yellow jersey standings will only actually test each other where the race is hardest and team dynamics play less of a role. In general, that means about two-thirds of the race is all but meaningless for the yellow jersey competition.

The money stages come in two types: Mountains and time trials. Those are the only two stage formats where the pack isn’t faster than the individual (in the latter case because each rider completes the circuit alone), and the only places where big time gaps open up. Now, the Tour can be lost anywhere. One loose cobblestone, one unsighted traffic circle, one ill-timed flat tire or bout of bronchitis and it’s all over. But in general, it can be won only in the mountains and in time trials.

This year’s Tour de France has seven mountain stages and two time trials, counting the Stage 21 mountain time trial as the latter but not the former. A race-ending time trial is not uncommon at one-week stage races or even the other grand tours.2 But the Tour de France hasn’t ended on a time trial since 1989, when Greg LeMond overcame a seemingly insurmountable deficit to Laurent Fignon to win the closest Tour in history. It’s arguably the most famous single day of racing in the history of the sport.

The last time a Tour de France ended on a time trial before that was 1968, when Jan Janssen—you guessed it—took the yellow jersey on the final stage and set a new record for smallest margin of victory.

Usually, the Tour de France ends with a bunch sprint on the Champs-Élysées, but this summer, the Olympics start in Paris five days after the Tour ends, which means the Champs-Élysées are otherwise engaged, and the Tour will end in Nice.

Since I’m already talking about the time trials, let’s start with those. The first is 25 kilometers of flat-ish terrain on Stage 7. The Stage 21 time trial is a mountain time trial from Monaco to Nice, covering 34 kilometers with two marked climbs: an 8.2 kilometer climb to La Turbie with an average gradient of 5.7%, followed by a shorter, sharper climb to Col d’Eze (1.6 kilometers at 8.8%). Given the amount of climbing and the weight differential between a time trial bike and a climbing bike, I’d expect the riders to start on a regular bike and switch to a time trial bike after Col d’Eze, as such bike changes have become de rigeur in time trials with lots of climbing.

As for the mountain stages, here are the ones to look out for:

Stage 4: Pinerolo to Valloire in Italy, 138 kilometers. Includes climbs to Sestriere (39.2 km at 2.3%) and the Col du Galibier (22.9 km at 5.1%). Both peaks are over 2,000 meters in elevation, which is the dividing line where high-altitude performance starts to make a difference; the Galibier is more than 2,600 meters above sea level.

Stage 14: Pau to Saint-Lary-Soulan in the Pyrenees, 152 kilometers. Includes the Col du Tourmalet (18.9 kilometers at 7.4%, 2,114 meters in elevation) and ends with a summit finish on the outside-category climb3 to the Pla d’Adet ski resort.

Stage 15: Loudenvielle to Plateu de Beille, 198 kilometers. Includes four first-category climbs, beginning with the Col de Peyresourde, and ends with a summit finish at Plateau de Beille after a 15 kilometer, 7.8% climb.

Stage 19: Embrun to Isola 2000 in the Alps, 145 kilometers. Starts with a climb of the outside-category Col de Vars (18.9 kilometers, 5.6%, 2,105 meters of elevation) before going up to Cime de la Bonette, which at 2,798 meters above sea level is the highest peak ever visited by the Tour de France and the third-highest paved road in the entire Alps. It’s about 2,000 feet higher than any mountain in the U.S. easy of the Rockies. And after a descent, there’s another first-category climb to another summit finish. Cime de la Bonette is so big, and the final climb is so long, that someone who gets into trouble here could lose enormous amounts of time on this stage.

I don’t want to hype up Cime de la Bonette too much, but this needs to be said. Mont Ventoux4 has this scary reputation in cycling because nothing grows above a certain altitude, giving it this austere, scary bare summit with horrific winds. Cime de la Bonette has that too, except it’s jet black.I’d be afraid to drive up this thing, much less ride a bike.

Stage 20: Nice to Cole de la Couillole, 133 kilometers. Four categorized climbs—a second and three firsts, followed by another summit finish. This stage doesn’t get over 1,700 meters, which means the riders will feel like they’re breathing soup after Cime de la Bonette the previous day, but there is zero flat ground between the four climbs—it’s all up-and-down, which will make it hard for teams to use their numbers to track down early attackers. Plus, as the last mass start stage of the Tour, everyone will be looking to get one last shot in before the final time trial.

Now, out of the 176 unfortunates who pin on race numbers this weekend, the overwhelming majority are going to be happy just to get over all these hills and take the figurative checkered flag in Nice in three weeks. They’re in it for stage wins, or to help a teammate, or just to get their sponsor’s name on TV. They don’t have a prayer of challenging for yellow.

Only four of the riders on this startlist—Jonas Vingegaard, Tadej Pogačar, Egan Bernal and Geraint Thomas—have ever won the Tour de France before. Only five others—Richard Carapaz, Primož Roglič, Jai Hindley, Simon Yates, and Remco Evenepoel—have won one of the other grand tours before. Maybe five or six others have a realistic shot at being competitive, but the overwhelming expectation is that the GC will be won by one of four riders: Vingegaard, Pogačar, Roglič and Evenepoel.

Still, let’s go down the list and touch on the riders I expect to end up in or near the Top 10, starting with the outsiders and working up to the favorites.

Felix Gall, Austria, Decathlon AG2R La Mondiale

One of the breakout stars of last year’s Tour de France, he rode his way into team leadership after Ben O’Connor gassed early in the race, taking a stage and leading the king of the mountain standings for a minute before settling into eighth place. The results since then have been a bit lackluster, but he got over the big mountains very well last year and another top-10 finish wouldn’t surprise me.

Pello Bilbao, Spain, Bahrain-Victorious

A sprightly, late-blooming climber. Just 5-foot-6 and 132 pounds, his slight frame will be an asset the higher up the race goes. At 34, he’s emerged as a decent grand tour rider in the past six years, with five top-10 finishes and three stage wins between the Tour and the Giro. Not dynamic enough to be a threat for yellow unless all four of the favorites go to pieces, but could end up in the top five if everything breaks right.

David Gaudu and Lenny Martinez, France, Groupama-FDJ

It’s been almost 40 years since a French rider won the GC at the Tour, and the wait will continue. Gaudu and Martinez are both outstanding climbers, but lack the power and time trial ability to mount a real GC challenge. It’ll be interesting to see how they divide their attention between challenging for stage wins and maintaining their position in the GC standings.

Enric Mas, Spain, Movistar

The current Great Spanish Hope, Mas is a three-time runner-up at the Vuelta and two-time top-10 finisher at the Tour. He’s a very, very good climber, a solid time trialist, and despite working for the New York Mets of cycling teams generally keeps a pretty cool head. He’s got about 99 percent of what it takes to win a grand tour, which in this field—one of the strongest ever assembled—is good for about fifth place on GC.

Simon Yates, United Kingdom, Jayco-Alula

Won the Vuelta in 2018 and has occasionally been a devastating stage hunter when he gives up on his GC ambitions. But his performance at grand tours has been inconsistent since then; he’s only finished two grand tours in the 2020s, but in those two races he came in third and fourth.

Jai Hindley, Australia, Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe

Aleksandr Vlasov, Russia, Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe

Adam Yates, United Kingdom, UAE Team Emirates

Juan Ayuso, Spain, UAE Team Emirates

João Almeida, Portugal, UAE Team Emirates

Pavel Sivakov, France, UAE Team Emirates

Matteo Jorgenson, United States, Visma-Lease a Bike

Part of the reason the Big Four are so entrenched is that at least half a dozen second-tier GC contenders have been scooped up by those elite riders’ teams to work as domestiques. They’ll be pacing their teams leaders over all those monster climbs and working to close down attacks and play the tactical game. And these are some big guns: Ayuso and Jorgenson are two of the hottest young GC riders on the planet. Yates finished third in last year’s Tour and wore the yellow jersey in the first week while supporting Pogačar. Hindley5 also briefly led last year’s Tour and won the Giro in 2022.

While it’s extremely common for a team to switch leaders mid-race based on form, the top contenders’ teams are so invested in their big guns that it’d take an actual physical disability—i.e. a crash and injury—for those priorities to change on the fly. And I’ll get to that shortly, particularly with respect to Jorgenson.

Tom Pidcock, United Kingdom, and Carlos Rodríguez, Spain, Ineos Grenadiers

So as much as I think there’s a massive dropoff in quality from the fourth-best rider in this race to fifth, every one of the top four has some major outstanding question mark. I’d be very surprised if all of them make it to Nice having completed a clean GC challenge. That means there’s a decent chance of a podium spot opening up, and this is where I think the serious challenge for that place begins.

Pidcock is an immense talent, a stupendous climber and one of the best descenders in the world, in addition to being a world cyclocross champion and an Olympic mountain bike champion. He won on Alpe d’Huez two years ago, though in 2023, in his first season as the leader at Ineos, he came up short. The British team, which won this race seven times in eight years from 2012 to 2019, was forced to call an audible for Rodríguez, who won a stage and ended up fifth on GC.

And make no mistake, these two—not Thomas and Bernal, the two former champions—are the main Ineos threats. Thomas podiumed the last two Giros, but this year his third-place finish came more than 10 minutes behind Pogačar. He’s not closing this gap with another grand tour already in his legs. Bernal, for his part, is more competitive than he’s been since his near-fatal training crash in 2022—he just finished fourth at the Tour de Suisse—but he’s still not the same guy who stormed to two grand tour GC wins before he turned 25.

Richard Carapaz, Ecuador, EF-Education EasyPost

El Jaguar has never quite broken through into the Pogačar-Roglič-Vinegegaard-Evenepoel superhuman club, but he’s come close repeatedly. He won the Giro in 2019 and has three other grand tour podiums. That includes a second place in the 2020 Vuelta where he was probably better than Roglič on balance, and a third place at the 2021 Tour where he was best-of-the-rest behind Pogačar and Vingegaard. Plus an Olympic road race gold medal, six grand tour stage wins, two turtle doves and a partridge in a pear tree. He’s one of my favorite riders to watch because he’s a proactive, dynamic climber who—and this is rarer than you’d think—has the rare gift of being able to complete a stage race without throwing some kind of a tantrum.

Carapaz was gearing up for a big Tour last year until he broke his kneecap in a Stage 1 crash. (Cf. You Can Lose The Tour Anywhere.) And since leaving Ineos for EF two years ago he hasn’t been able to deliver the same splashy results. But he also hasn’t really gotten the chance. Peak Carapaz is closer than anyone to that group of favorites—especially if you take the favorites’ teammates out of the equation—it’s just a matter of whether we’ll see him race.

On to the Big Four.

Remco Evenepoel, Belgium, Soudal-Quick Step

On paper, roughly 60 kilometers of time trialing would seem to suit the defending world time trial champion. If he were going up against basically any other set of grand tour riders, I’d chalk that up as a massive win. But there’s a weird rock-paper-scissors thing going on with these four and time trials. Evenepoel is the world champion, as I’ve said, and if I had to choose any of these four to win a time trial I’d pick Remco without thinking twice.

But Roglič is an Olympic champion. Pogačar won the 2020 Tour on the strength of a thermonuclear time trial to beat Roglič,6 but Vingegaard beat Pogačar in the Tour de France time trials two years running. That includes a decisive ass-whooping in Stage 16 last year the likes of which Pogačar has taken, like, twice in his entire career.

But in last year’s Vuelta, Remco put a minute into Vingegaard in the time trial, but only 19 seconds into Roglič. So I don’t fuckin know. Particularly with this much climbing on Stage 21.

Wow, it just hit me how ridiculous that stage is going to be if this race is at all close coming into the final day. LeMond-Fignon ‘89 could end up looking downright predictable.

So here’s why I have Remco fourth. He’s never raced the Tour before. His one grand tour win, the 2022 Vuelta, came against a field with no Pogačar and no Vinegegaard. Roglič DNF’d and Carapaz went for the king of the mountains jersey. In his title defense, Evenepoel was highly competitive against Vinegegaard and Roglič for, oh, about 20 of the 21 stages. But on Stage 13 he blew up in a manner that is, frankly, shocking for this level of GC rider, and lost 27 minutes.

To Evenepoel’s credit, he pivoted to seeking stage wins and had a huge back half of the race. He won two stages and finished second in another, won the mountains classification, and almost sneaked back into the top 10 on GC. But 20 good days out of 21 won’t cut it at this level. A win is absolutely possible, but I’m not convinced Remco can do it without help.

Jonas Vingegaard, Denmark, Visma-Lease a Bike

If I knew Vingegaard were healthy, I would put him no. 1 without hesitation. If he is at 100 percent and doesn’t crash he will win this race. But a little less than three months ago, Vingegaard, Evenepoel and Roglič were among those who got wiped out and tossed into a concrete culvert at the Tour of the Basque Country.

All three were badly injured, but Evenepoel and Roglič were able to return to action at the Critérium du Dauphiné, while Vingegaard—who suffered a punctured lung, broken ribs, and a broken collarbone, has not turned a pedal in anger since the accident.

His DS, Merijn Zeeman, when announcing Vingegaard’s return for the Tour, was circumspect: “Of course, we don't know how far he can go yet. We are being cautious because he has not been able to race, and his preparation has been less than ideal, to say the least. But he will be there, healthy and motivated.”

Maybe it’s sandbagging, but I’m not optimistic. Add to that the state of his team. Sepp Kuss, the American climber who won last year’s Vuelta after shepherding both Vingegaard and Roglič to numerous grand tour wins, got COVID at the Dauphiné and hasn’t recovered in time to take the start. So while Vingegaard’s support system is still strong—I’d take Jorgenson, Wilco Kelderman, and Wout van Aert over Remco’s teammates—he’ll be without the best support rider in the peloton. Plus I kind of hate the blue special jerseys Visma-LAB is wearing to the Tour.7

Placing Vingegaard third is a bit of an odd hedge. I don’t think he’ll finish third—I think he’ll finish first, second, or not at all—but I just don’t have enough information to be sure.

Primož Roglič, Slovenia, Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe

Plus there’s this other thing about Vingegaard.

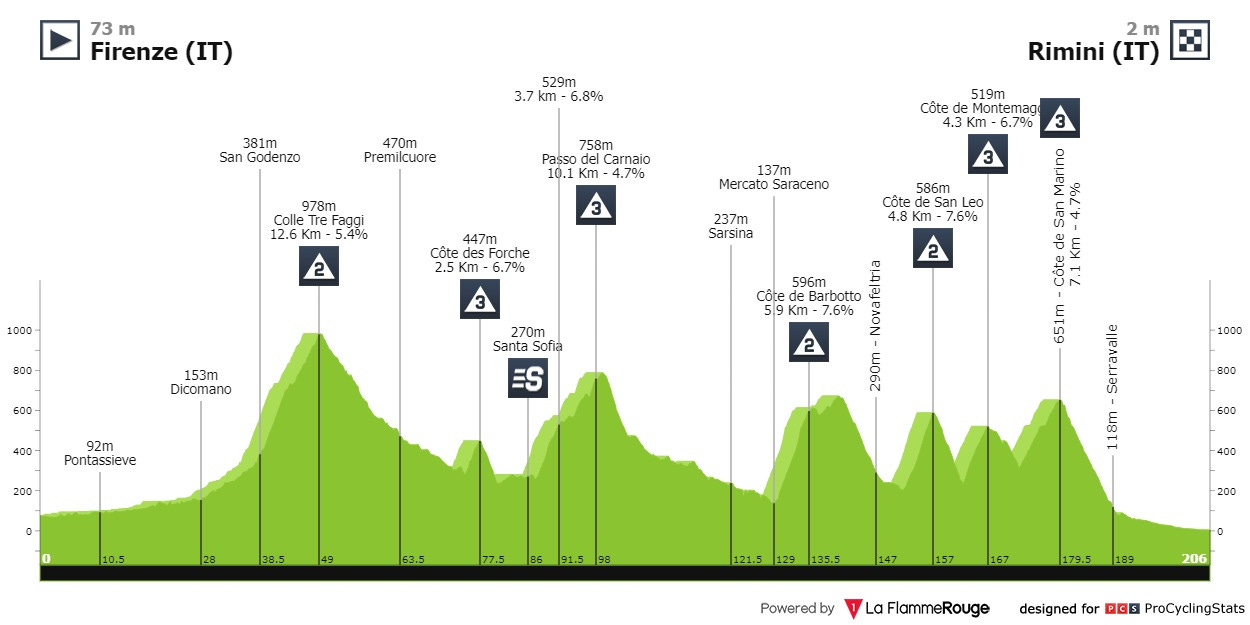

This is the parcours for Stage 1. It’s a ton of climbing. No particular climb is going to give any of the GC guys trouble, but we’re looking at seven Cat-2 and Cat-3 climbs on the very first day of racing, when nobody—perhaps not even Vingegaard himself—is sure of his fitness level.

I talked about how all of these guys are good in the high mountains and on time trials. Vingegaard is better than Pogačar in the heat, and if he survives to Week 3 and all those long, grinding efforts in the mid-July sun over 2,000 meters’ elevation, he’ll be in business.

But Vingegaard is a classic GC rider. He’s built like one of those fiberglass solar-powered cars: About as thick and broad as a sheet of construction paper and not much heavier. That’s great for long, metered efforts, but he lacks the explosiveness of his three big rivals. Pogačar, Evenepoel, and Roglič have all won Liège–Bastogne–Liège,8 whose repeated up-and-down short climbs resemble first couple days of racing in Italy.

Ordinarily: Who gives a shit? That’s not where the Tour de France is won and lost. Vingegaard has always lost a few seconds here and there to Pogačar on short climbs and sprints for bonus seconds. But the past two years he’s clawed it all back with time to spare on one or two big, steady efforts.

This year, I think all three of the other guys are going to gang up on Vingegaard right away and really put the screws to him on terrain that favors them and disfavors the two-time defending champion. Especially because, with Vingegaard under-raced and recovering from injury, he might be at his weakest early in the race.

Here’s the other thing: Attacks on this stage could force Visma-LAB to make the most important tactical decision of the entire race on the first afternoon. This parcours doesn’t suit Vingegaard, but it does suit Jorgenson. It very closely resembles Stage 8 of this year’s Paris-Nice, where Jorgenson wrapped up the overall win—the biggest of his young career by far—because Evenepoel couldn’t shake him over several climbs.

So let’s say Evenepoel and the two Slovenians get a gap on Vingegaard early. Does Visma-LAB send Jorgenson along to mark the move? Or do they keep him behind to pace Vingegaard back, since without Kuss their bench strength is limited?

Anyway, this is ostensibly about Roglič, who’s been champing at the bit to get this chance ever since Pogačar stole his yellow jersey in 2020. At 34, he’d be one of the oldest Tour de France winners ever, but with Hindley and Vlasov in his corner he’s got an incredibly strong team and sole, undisputed leadership of same. That last is incredibly important, as his final two years with Jumbo-Visma9 were peppered with disputes with Vingegaard over team leadership.

Tadej Pogačar, Slovenia, UAE Team Emirates

My questions about Pogačar are…well, there’s only one, really.

Pogačar is out to win the Giro and the Tour in the same year, which hasn’t been done since 1998.10 Well, he’s actually out to win the Giro, the Tour and the world road race championship, which hasn’t been done in the same year since 1987, and only twice ever. Well, if we’re being honest, he’s trying to win the Giro, the Tour, the world championship and the Olympic road race in the same year, which has obviously never been done.

So, is he tired from the Giro?

Given the easy with which he won—six stage wins, 20 stages in the pink leader’s jersey, and a nine-minute, 56-second margin of victory, the largest in 59 years—I’m inclined to think Pogačar did not unduly exert himself at the Giro. Certainly no more than Evenepoel, Roglič, and Vingegaard did while recovering from that horrific crash. More than that, he really hasn’t raced that much. He’s only participated in five races this year, which goes under the radar because all of them were huge, high-profile events and he’s won four of them: the Giro, Strade Bianche, Liège–Bastogne–Liège, and Volta a Catalunya.

All told, that’s 31 days of racing. Rodríguez, just to take one example, has had a more traditional spring for a Tour de France contender: A few one-week stage races, plus some second- and third-tier racing in Spain in February just to get his legs warmed up. Rodríguez has raced 33 days. It’s possible Pogačar’s all-killer, no-filler schedule has kept him fresh enough to go 12 rounds with the best in the world for the yellow jersey.

I just can’t imagine the guy I saw in Italy this May—to say nothing of how he sleepwalked to victories at Strade and Liège–Bastogne–Liège earlier this spring—losing to anyone. And in circumstances such as these, the only threat to Pogačar in a stage race is a completely on-form Vingegaard in hot-and-high conditions. And as I said earlier, I am not sure we’re going to see that.

The one thing I am sure of is that Pogačar, who has raced with an almost sarcastic aggressiveness all spring, is going to test Vingegaard at the very earliest opportunity. I would all but guarantee a Stage 1 gang-up on the wounded champion if only because it’d be so in character for Pogačar to want to test his rivals.

This—the strongest rider on the strongest team—is the man to beat.

Predicted Top 10:

Pogačar

Vingegaard

Roglič

Evenepoel

Carapaz

Mas

Ayuso

Jorgenson

Pidcock

Bilbao

Including bonus seconds, but that’s not quite as poetic

Three-week stage races: the Tour, the Vuelta a España and the Giro d’Italia

Climbs in cycling races are ranked by difficulty, from 4 (easy) to 1 (hard). Outside-category (or hors categorie, HC for short) climbs are too hard to rank.

Which the Tour doesn’t visit this year, though it makes frequent appearances

Also, the long-awaited injection of Red Bull money to Bora-Hansgrohe has finally come through, with a double-hyphenate title sponsor and yet another dark jersey in place of the brilliant old two-tone green Bora kits. I’m a little pissed, and I’m giving myself until the end of the Tour to figure out if I want to just go with calling it Red Bull or come up with a snarky nickname.

He also put in some monster time trial mileage at this year’s Giro, which will go unremembered because he was so much better than the rest of the field in the mass start stages.

They usually wear yellow, but the organizers make them wear a change kit so as not to be confused with the race leader’s jersey.

The oldest of the Monuments, the five most prestigious one-day cycling races

Now Visma-Lease a Bike

With PED caveats pulling in about nine different directions