Inside Every Skier, There's a Cyclist Trying to Escape

Great cyclists are born, but they can be made late

The big cycling news over the weekend was the women’s Tour Down Under. On Friday I predicted that defending champion Grace Brown would win; not so, Brown finished 42nd. But I did pick the winner’s nationality and the decisive climb—23-year-old Australian Sarah Gigante landed on the top step of the podium by smashing her opponents on the climb of Willunga Hill.

Gigante was a three-time national champion at age 20, but health issues caused her to basically write off the past two road racing seasons. Her ascent of Willunga seems to indicate a return to previous form. Maybe I should’ve seen this coming because the climb literally has her name on it.

One fun thing about cycling is that all the major race venues on public roads, and over the past few years, it’s become more and more common for top pros to post their workouts and even race data to Strava. That means anyone in the area with a bike and the app can test themselves against the professionals, who sometimes get territorial about KOM and QOM titles on their home climbs.

A lot of people on Twitter say a lot of stupid shit about baseball, football, and basketball because they don’t appreciate how good even the worst pros are just by watching them on TV. In cycling, any loudmouth is welcome to go try their luck against any pro rider. It’s very democratic.

This whole article isn’t going to be about Gigante and Willunga Hill, but I want to highlight her effort first.

On a climb of any serious length, there are two phases of racing: A pacing stage, in which riders will go on the front of the lead group and ratchet up the tempo to drop any dead weight. Nothing too explosive, just a steady, fast pace. And once the ground is softened up and even the best climbers are starting to wear out, only then does a proper attack come. It’s like sending the infantry in after an artillery barrage.

For big mountains, climbs of 20 kilometers and almost an hour, this is a team effort. A team leader needs two or three teammates to thin the herd before attacking him or herself.

Willunga hill is only three kilometers long, and Gigante’s course record is eight minutes and 13 seconds, so she was able to do both the grinding and the attacking all on her own.

The clip above is a perfect illustration of how this works. Gigante had worn out race leader Cecilie Uttrup Ludwig, who was hanging onto Gigante’s wheel for dear life. (The Tour Down Under leader’s jersey is orange, not yellow. Race organizers call it “ochre” either to be difficult or because “ochre” sounds way cooler than “orange” in an Australian accent.) Gigante looks back, sees her opponents starting to yo-yo out of touch, and just floors it.

Real “I must go now, my planet needs me” shit that really illustrates the power these riders have at their disposal for big attacks, as well as the difference between a rider who’s cracked and one who still has some gas left in the tank.

But on to the main issue, which comes from a comment on Friday’s post by Brendan Dentino, a fellow South Jersey man who writes the Out in Left newsletter. (Help me come up with content and I’ll plug your work: That’s the Wheelysports guarantee.) Says Brendan:

I would be interested to know how people get into cycling/become elite cyclists. Like, what’s the cycling equivalent of signing your five-year old up for t-ball and watching them become Bryce Harper?

Great question.

If you want your toddler to win the Tour de France, buy them a set of skis.

Cycling, perhaps more than any other sport of its size, is one that even elite athletes can come to relatively late.

I’m going to compare cycling here to baseball, Formula 1 and hockey, not just because those are the other sports I’ve covered extensively, but because they all require prospective elite pros to start early. These sports require highly-tuned perception and fine-motor control in order to operate at the top level, as well as highly specialized equipment and facilities on which to train. (Extremely expensive equipment and facilities, in the latter two cases.)

Cycling, by contrast, is relatively simple. Not to say that there aren’t substantial intellectual and technical challenges to the sport, but someone with the underlying physical skills can learn the really subtle elements of technique as a teenager or even as an adult. Things like time trial positioning, tactics, or conditioning. Professional teams are not only well-equipped to teach these things, they’re frequently happy to get their hands on raw talents who need to learn them.

There isn’t really a cycling equivalent to a baseball player getting to triple-A and realizing he can’t pick up spin, or a driver getting to Formula 2 and overheating his tires.

The closest thing I can think of is that there are stage racers—Tejay van Garderen and Thibaut Pinot spring to mind from the previous generation—who were elite over one week but just could not put it all together for three weeks, and therefore consistently disappointed at grand tours. Even then, both had highly decorated professional careers anyway. Recovery on the level of a grand tour contender is a luxury, even for most pros.

What all this means from a practical standpoint is that the skills that make a future Tour de France or Paris-Roubaix winner can in many cases be honed without even touching a bicycle. Many pro cyclists don’t even realize that they have a future in the sport until their late teens.

With that said, there are plenty of cyclists raised essentially from birth. As with most sports, children of pro athletes are likelier than normal to follow in their parents’ footsteps not just because of genetics, but because they’re given access to the sport at a high level at a young age. Mathieu van der Poel is probably the most famous: His father won two monuments and a cyclocross world championship, while his grandfather was legendary French cyclist Raymond Poulidor. Joseba Beloki’s 18-year-old son Markel turned pro this year. Eddy Merckx and Francesco Moser both had sons in the pro peloton.

Youth cycling isn’t as organized as other sports, but plenty of riders got exposed to the sport at a young age. In addition to van der Poel’s famous father and grandfather, his older brother was a pro cyclist. So was Peter Sagan’s. Tadej Pogačar followed his older brother to a local cycling club, as did Marianne Vos. Egan Bernal was introduced to cycling by his father, who was an avid hobbyist.

As far as formal racing goes, cycling clubs will offer youth criterium races, while some kids get their start as either youth cyclocrossers or, like Bernal and Sagan, mountain bikers, before transitioning to the road. Being exposed to the sport is great; being exposed to the activity at all is the most important thing for a future racer.

In the United States, formalized road cycling—clubs, group rides, criterium racing—is viewed as a bourgeois sport. It’s a hobby for doctors lawyers who can afford to drop four figures on a fancy bike so they can stay thin for their second wives.

But what is a bicycle, globally? Not a specialized piece of sporting equipment, like a baseball glove. For most people across the world—especially children—a bicycle is the cheapest, most accessible form of high-speed transportation known to humanity. And while there are certainly plenty of pro cyclists who come from affluent backgrounds, others came from poor families and got good on a bike because that’s they only way they could get around.

Nairo Quintana is the best example I can think of. He became one of the best climbers of his generation not through any regimented training but because he grew up 9,000 feet above sea level and getting to school and back was a 20-mile round trip. You want your kid to become a good cyclist? Move to the Andes and make it so if they don’t get over that mountain they can’t come home from class every day. Practice makes perfect.

In reality, what a kid does from age five to 16 or 18—or in some cases, even up to age 25—has little impact on their professional cycling future, as long as they meet the physical requirements of the sport as a young adult. Professional cyclists vary in their abilities and gifts, but there are a few fundamental building blocks they all share:

Size. The top riders in the men’s peloton vary in height from around 5-foot-5 to 6-foot-6, but they’re all skinny. You’ll see pro cyclists come to the sport from all over the place, but there isn’t very much overlap with football or basketball. (Chloe Dygert is the only example that comes immediately to mind, but she’s tall for a cyclist and relatively short for a basketball player.)

Cardio. Obviously.

Leg strength. Again, obviously.

Basic bike handling. Riders eat, drink, receive medical attention and bike repairs, and put on and take off raincoats while in motion. A couple years ago Julian Alaphilippe changed his shoe on the fly at Liège–Bastogne–Liège. Pro cyclists stay on their bikes the way wildebeest stay on their feet.

There are some riders for whom bike handling is a strength, and it’s a differentiating factor for some who can descend faster, corner faster, avoid crashes. But the standard of competence is not as high as you’d think. Jonas Vingegaard’s discomfort with taking both hands off his handlebars has become a meme, and this is only the best stage racer in the world right now.Mental toughness. This applies in two areas. First, and most commonly celebrated: Perseverance. The ability to dig deep when tired or injured, to maintain technique and awareness while the brain is starved of oxygen. The second is comfort with speed. The easiest moments in the competitive calendar come at 30 miles an hour across uneven roads while riding shoulder-to-shoulder with 100 other racers. You can’t freak out in that situation and be a pro cyclist. Pro cyclists—especially climbers and GC specialists—have to be comfortable cornering at high speeds on unfamiliar roads while descending. I’m highlighting these attributes perhaps because I absolutely do not posses them myself.

I know I say “the cool thing about cycling is…” about twice a newsletter, and I’m sorry, but one cool thing about cycling is how many athletes come to it late in life, from other sports.

Because apart from bike handling, you can learn these skills anywhere. Any sufficiently small athlete with meaty quads, big lungs and a high tolerance for pain can become a professional cyclist if they want to. If they can run all day, or ski all day, or skate all day, they can probably bike all day too.

It’s shockingly common for young athletes to take up cycling—either as cross-training for a different sport or after a career-ending injury—and wind up in the pro peloton. (Cycling is highly dangerous in terms of impact injures, but you’re not going to tear your labrum or your ACL doing it.)

Here’s a partial list:

Skiing: Greg LeMond, Tyler Hamilton, Quinn Simmons, Primož Roglič

Soccer: Remco Evenepoel, Annemiek van Vleuten, Veronica Ewers

Triathlon: Lance Armstrong

Track: Mike Woods

The best one is speed skating. I mentioned this in the capsule about Demi Vollering in December, but there’s so much physical overlap between cycling and speed skating—they’re both lower body-based cardio activities that place a premium on smooth motions and aerodynamics, plus both sports give the Dutch an enormous cultural boner—that some top athletes have flitted between the two almost interchangeably.

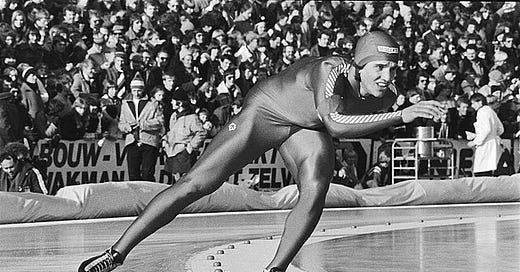

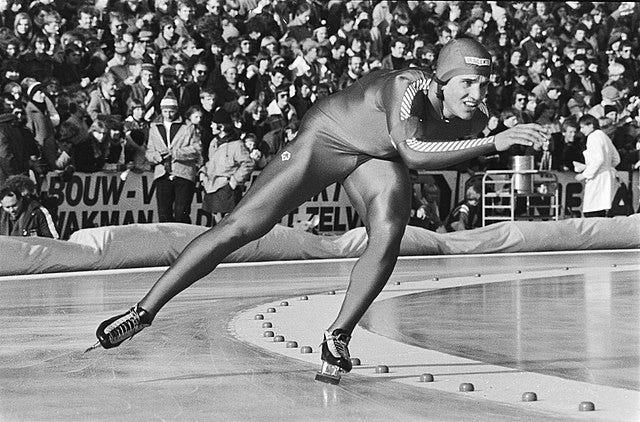

Which explains the black-and-white photo of the guy in the bodystocking at the top of the post. That’s Eric Heiden, who’s most famous for winning five speed skating gold medals at a single Olympics in 1980. What’s less well-known is that Heiden had a second career as one of the first American cyclists to make it in the European peloton.

Heiden also has a younger sister, Beth, who was herself a world champion speed skater and won a bronze medal at Lake Placid. Six months after winning an Olympic medal on the ice, she got on her bike won the world road race championship, a feat unprecedented at the time by any American—male or female—and to this day unmatched by any other American woman.

Not having studied the issue scientifically, I can’t say for sure, but I imagine the easy with which athletes from other sports can transition to cycling—and the relative paucity of opportunities for organized youth racing, at least in the U.S.—helps prevent burnout.

Few things in sports make me cringe as much as an athlete who seems to have been raised in a test tube to excel at a specific sport. For every Max Verstappen, you get 10 Pete Maraviches (the experiment works, but at what cost?), 1,000 Todd Marinoviches, and 100,000 19-year-olds you’ll never hear of who are completely broken socially and psychologically.

If you were a total sicko parent and you wanted to train your kid up to become a cyclist (first of all, don’t, the money’s way better in almost any other sport), I’m not sure how you’d go about doing it. Short of just forcing the kid to ride six hours a day.

Multi-sport athletes are less likely to burn out in general, but it makes sense that athletes who excel in cycling as adult pros would come to the sport on their own. In pro cycling, even the racing is monotonous and miserable, let alone the training. And the extent to which this sport takes over an athlete’s life—from diet to energy conservation to submitting to doping control—is basically unparalleled in sport.

In short, reaching a professional level in road cycling requires time and commitment that I can’t see someone putting in unless they really, absolutely love it. A six-year-old can’t really make that decision, but a teenager can.

So how do you build a Tour de France winner from the ground up? Move to the mountains and take off their training wheels early. Then sign them up for soccer.

Six years before winning Norway's first Tour de France victory, in 1987, Dag Otto Lauritzen suffered a parachute accident at the age of 25 that could have amputated his right leg. He then started cycling to help his rehabilitation. I don't know if he was previously involved in athletics.